Knots

- Dr. Vin

- Jun 27, 2020

- 3 min read

Updated: Jun 29, 2020

Over eggs and toast at the dining room table, my husband and I compare where we are in the autobiographies we are separately reading. These are books from two prominent black men born in the 1920’s in the USA.

“As a young man James Baldwin saw there were 2 choices for him growing up in Harlem, joining a world of crime or a world of church. He became a young Christian minister.”

“Well, Malcolm X was raised with the same options, went into crime, meets Elijah Mohammed, then goes from a world of crime to a world of church, The Nation of Islam.”

“Baldwin eventually realizes he is being used in a power game, becomes disillusioned and leaves the church. When Baldwin meets Elijah Muhammed, he understands his appeal but is not drawn into his orbit.”

“Malcolm X’s rising power in the Nation of Islam was a threat to its leader, Elijah Muhammed. In all likelihood, Muhammed had him assassinated.”

As two white people, we are striving to broaden our view by listening to the voices of black lives. As a somatic psychotherapist, I am interested in how trauma affects the body. A colleague shared an interview of Resmaa Menakem, a clinical trauma therapist. When he was young, Resmaa was massaging the chubby hand of his petite grandmother and asked her, “Why are your hands fat, Grandma?” She said, “Picking cotton.” It was in the weary and constricted tone of her voice that he could feel the trauma that she had lived. His book is “My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies”.

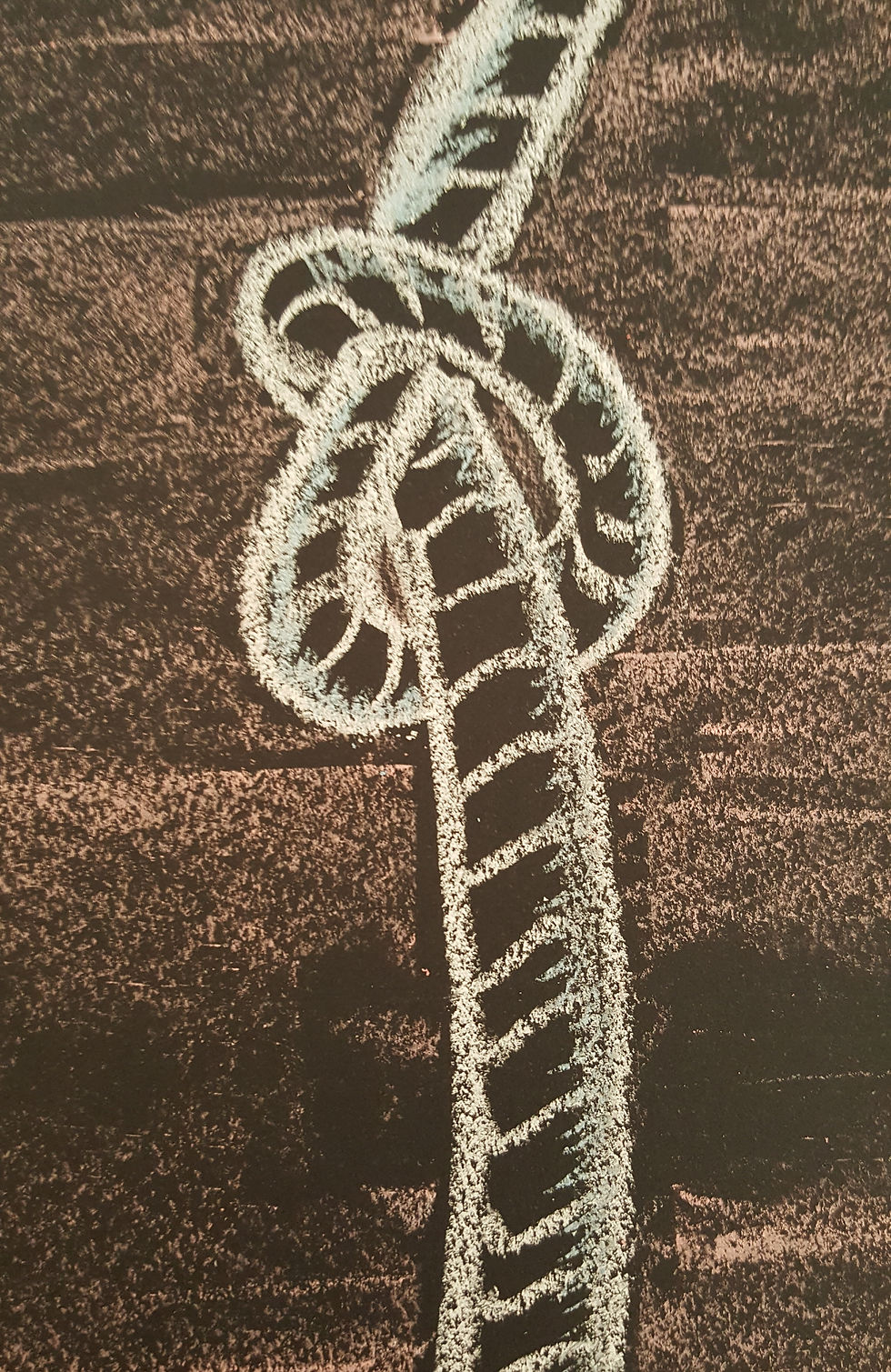

Menakem talks about the ways we hold our own race and see others. For examples he says, “black body sees white body as privileged, controlling and dangerous…Police bodies see black bodies as often dangerous or disruptive, as well as superhumanly powerful and impervious to pain. Our nervous systems are in knots.”

One solution is to return to the body. This may include uncovering intergenerational trauma. If you are born to people already braced, (like Menakem’s grandmother) you pick up this lockdown in your psoas muscle, (like a tightening deep in your gut), and you brace but it is often decontextualized, often unconscious.

Here is a somatic practice that Menakem shares to “discover what lands and what is still in the air”:

Sit and orient to the room (look around versus waiting for danger).

Look straight ahead. Register what you see.

Next, twist, look over your left shoulder, turn your hip ( this engages the neck and psoas);

Notice what you experience. Return to center.

Look over your right shoulder.

Notice what you experience. Return to center.

I tried this. I felt various feelings. I felt cocky, I felt fragile, and I worried about some teens I know, the rich white ones, the poor white ones, the black ones.

I was working with a young, black male recently. I noticed his eyes veiled and almost shut, his head tilted down and I asked him about this. He said, “I walk with my head down and don’t open my eyes in public.” I thought of how Holocaust victims in the camps were not allowed to look up. The men were ordered to wear a hat, keep their heads down and not look at the guards. They had to keep their hands out of their pockets – under threat of immediately being shot. There is a now a statue at Dachau of a Jewish prisoner. He has no hat, his head is up, his eyes are open, he looks proud and his hands are in his pockets.

Menakem uses an image to support somatic healing. “Like when you pick a car, then go buy it, then notice them on the road and you never noticed them before. That is the promise of following your body, with its signs of trauma, signals of safety and danger. Once you pause and pay attention, you can bring your fears, rage, familial traumas to consciousness, and then begin to heal. We then have the opportunity to see through another person's eyes."

Blindness helps us tolerate injustice. We stay ensconced in our tribe for safety. We have always chosen safety over danger, so that makes sense. But we need to tolerate some danger by walking toward the electrified fence that keeps us interned in our camp. We need to look through that fence and see what lies outside it. This country is embroiled in division and we need to change the system. One strategy is by going inward and wrestling with the demons we each carry in our own souls and guts.

Comments